Conversation with Deema Assaf

The Jordanian architect who makes the forests grow.

Words: Mouna Anajjar. Photography: Tayyūn.

Landscape around North of Jordan.She planted her first Miyawaki forest in autumn of 2018. Since then, the 37-year-old Jordanian architect, along with her Japanese sociologist colleague, Nochi Notoharu, has helped two others sprout from the ground. Their weapon against climate change is the “Miyawaki Method”, which can restore lost native forests in record time–10 years–by recreating dense mini-environments rich in biodiversity. She gives us the scoop.

MOUNA Hello, Deema. Why don’t you start by introducing yourself. Deema Assaf: who are you?

DEEMA Like most people, I am an ever-evolving blend of so many things. On a professional level, I am an architect, urban forester, independent researcher, and an avid student of native plants and the natural world. I am founder and director of Tayyūn, an Amman-based research studio exploring urban rewilding and regeneration of urban ecosystems through native forest creation and cross-species architecture.

M Tell me a bit about your childhood: where did you grow up? In what kind of environment?

D I spent most of my childhood in Amman, yet a quite different version from the congested city we see today. My childhood Amman was more of a small town than a big metropolis. Our neighbourhood only had a few houses scattered in between stretches of farmland and shrubland. And this vast open landscape was our playground. We spent most days out of doors collecting rocks, picking wildflowers, climbing trees, and hunting insects. Yet things changed as we got older. We no longer saw lizards during our bike rides, or toads while waiting for the school bus. We no longer heard jackals howling or crickets singing on summer nights. As Amman grows into a different reality, I consider myself lucky to have experienced this older version of the city.

M You first decided to study architecture. What motivated your choice?

D Growing up, I was the artistic child in the family. I always enjoyed painting, music, art projects and photography. On the other hand, I also enjoyed reading, science, and math – the latter not anymore. After finishing high school, architecture seemed like the right decision for me. It spoke to these two parts of me and brought them together. And I really enjoyed delving into the world of architecture: the philosophical, the social, the environmental, the moral, the political, the artistic, and the technical – with all its complexity. And I love the creative process of exploring possibilities, of seeing the unseen, and of visualizing and materializing ideas and visions.

M And then what happened?

D It was during a permaculture design course when I became deeply invested in regenerative landscaping and native forest creation. It all started as a personal interest in growing vegetables and saving heirloom seeds, and I could not have imagined that it would develop into something more. At one of the sessions, we were studying a video by Geoff Lawton of a 2000-year-old food forest in Morocco, and I became instantly obsessed. At first, as an architect, I found the space captivating: the forest had a beautiful interior with a high ceiling of green foliage, sleek tall pillars of palm trees, green walls of fruit trees surrounding a series of cool dark rooms with filtered light seeping in, falling onto the forest floor carpeted with shrubs and grass. And this living space was in fact man-made designed. I decided right then that this is what I want to do. My research on forest creation then led me to the Miyawaki method, developed by Japanese botanist Dr. Akira Miyawaki, which creates ultra-dense, highly biodiverse, multi-layered native forests, 10 times faster than natural succession. I found the method’s promise to restore the lost indigenous forests, that take hundreds of years to recover, in just a few decades beyond incredible. I could not think of anything more urgent and meaningful. Moving from architecture to urban rewilding and native forest creation simply felt like the right thing to do.

Jordan’s first Miyawaki forest: at planting, after 8 months, after 2.5 years.M Did you always have an ecological bent or an environmental consciousness? If not, at what age did you become aware of these, and what were the circumstances?

D I cannot single out a certain moment to be honest. Yet somehow, “Do No Harm” has always been a motto of mine. And I think environmental consciousness developed from a moral perspective for me. As a student, I was interested in the connections between urbanism and social justice. I investigated the ethical dimensions of the built environment and studied deep ecology in Islam and world religions. So probably then. And I always wanted to have a gentle presence on Earth, seeking regenerative practices, ethical consumption, reducing waste and recycling. Yet it is far from what it should be and will always be a work in progress.

M You started to be interested in native ecosystems and the effects of urbanization during your career as an architect. What questions and issues were you concerned by?

D As an architect, I was lucky to have worked on interesting projects and places, including World Heritage sites and national nature reserves. Yet with culturally and environmentally sensitive sites comes great responsibility. Despite our best intentions and efforts, we architects cause inevitable damage: we use stone from quarries; we build with high embodied energy materials like cement, steel and aluminum; we import supplies that travelled halfway around the world; we excavate soil that took thousands of years to develop; and we affect the native vegetation that peacefully coexisted for hundreds of years. We think it is a necessary evil, and that we can reduce these negative side-effects with sustainable design solutions and green building design. Probably. But I came to believe that the world needs a lot less structures and a lot more forests.

“Nature is in a constant state of change – always aiming at creating richer and more developed ecosystems.”

M Then you got the idea to create an entire urban forest. The project seems pharaonic. How did you handle it at the beginning?

D We are starting really small. Our first pilot site is only 107 square meters. And we are gradually building the database and infrastructure needed for native forest creation in Jordan. We are constantly testing techniques and decisions, always learning, refining, and fine-tuning. And we are lucky to rely on the collective body of knowledge developed by Dr. Miyawaki and his team in Japan, by the Afforestt team in India, as well as by numerous ecologists, botanists, mycologists and permaculturists from around the world.

M How did you discover the Miyawaki method?

D During my research, I came across Shubhendu Sharma’s TED talk about his work creating Miyawaki forests in India. And I was just taken by the dramatic transformation of landscapes from barren plots or artificial lawns to rich dense forests. I started researching the application of the method for Jordan and got in touch with Shubhendu-ji’s practice, Afforestt, and later joined their Miyawaki forest creation workshop in Rajasthan. And it was incredible to witness the growth of the forest we participated in planting in just a few months.

M Can you explain it to us as if you were explaining it to a 12-year-old? What does this method allow for its environment?

D Nature is in a constant state of change – always aiming at creating richer and more developed ecosystems. Where there is bare land, annuals appear, attempting to improve soil and increase organic matter content. If not interrupted, this mission would then be handed to more developed plants: herbaceous perennials, then woody shrubs, then small trees, bigger trees and so on until a complex mature forest takes over. And only then, change would be less needed. Nature favours the stability of this mature forest and allows it to regenerate for thousands and thousands of years. This process from bare to mature (aka, ecological succession) might take 100 – 300 years, yet with the Miyawaki method we can reduce it to 10 – 30 years. The acceleration of these natural processes is two-fold: first, through improving soil and building soil life that supports the growth of a developed ecosystem; and second, by researching and unravelling the components of the mature indigenous forest and establishing it from day one. (In more technical terms, researching the Potential Natural Vegetation to identify the climax plant community.)

M Why did you choose this method and not another one?

D Compared to conventional reforestation methods, Miyawaki forests are the closest model to natural forests. It is not merely about greening or planting “individual” trees; it is about establishing a complex and dynamic plant “community”. It is about creating a living soil with an active Wood Wide Web that allows trees to support and nurture each other. It is about re-connecting native species that co-evolved together for thousands of years. It is an evidence-based method that is rooted in a deep understanding of how nature works and evolves.

M When did you meet Nochi Motoharu? And how did you come together to create this project?

D I first met Nochi-san during a permaculture design course and then a second time during my research on the Miyawaki method. He had been living in Jordan for over a year at the time, so I expressed interest to know more about the method and also decided to join the workshop in Rajasthan. We then began working together and planted Jordan’s first Miyawaki forest in fall 2018. And it is more of a trio, actually, as our team includes Fumitaka Nishino, Dr. Miyawaki’s last disciple and our technical adviser, or a tribe, as our work would not have been possible without the help of numerous team members, partners, and volunteers.

Vegetation survey with Nochi Motoharu and Fumitaka Nishino at Birqish forest.M What was the process of applying this Japanese method to Middle Eastern soils, especially Jordanian ones?

D The Miyawaki method is very place-specific, always aiming at understanding, mimicking and accelerating the natural processes of any chosen locality. In Jordan, we do plenty of research for each site to understand its unique soil structure and characteristics, and to identify the best soil engineering intervention for forest creation. Ultimately, the method aims at restoring the native vegetation cover, and the indigenous plants of the land are perfectly attuned to its local climate and soil conditions.

M What criteria do you use when choosing a site to plant?

D It’s pretty simple: if it was once a forest, it can be a forest again. It’s in the land’s DNA.

M How many Miyawaki forests have you planted since then? And do you imagine planting more of them?

D We’ve planted three forests since the autumn of 2018, and we are definitely planning to plant many more of them.

M What are the major challenges?

D We face many challenges pioneering the implementation of this method in new territories. One of them is the lack of research and documentation on native ecosystems in Jordan. Another is the absence of necessary infrastructure and the unavailability of native plants in local nurseries. We are constantly striving to overcome these obstacles.

M Your research studio is called ‘Tayyūn’. Can you tell us more about the choice of this name, and what it means to you?

D Tayyūn is the Arabic name of a Mediterranean pioneer plant, Inula viscosa. And pioneers are nature’s first instruments to transition bare land into richer ecosystems. They can grow in disturbed soils and harsh low-fertility conditions, gradually building soil and paving the way for other plants to grow and take over. And unlike charismatic megaflora, Tayyūn is a rather small, often overlooked plant. It is a personal reminder of the quiet, patient, and hard work that needs to be done. It also has a strong fragrance that brings back so many memories from my childhood.

M You also host different workshops and educate volunteers about native ecosystems in Jordan…

D Many people express interest in our work and are eager to be part of restoring nature in Jordan. We thus organize workshops and offer volunteer opportunities where people from all walks of life can join tree planting, seed harvesting, and seed processing – creating encounters for them to gradually recognize the forms and scents of wild plants, build local knowledge, excitement, and weave the native plants of our land into their lives and memories.

M ‘Wild Edible City’ is among your other projects, what exactly does it consist of?

D Wild Edible City is a project that fuses research, urban foraging, nature education, creative conservation, and culinary art. It looks into the unexplored tastes and possibilities of Amman’s native species: from acorn flour and wild spices to forest-infused vinegars and wild pine syrup. It is a journey in the native foodscape aiming to explore the intricacies and delicacies of wild natives and to develop recipes that can be part of an Ammani wild cuisine.

Retam (Retama raetam) seed pods at harvesting season.M Do you have any other ongoing or upcoming projects that you want to share with us?

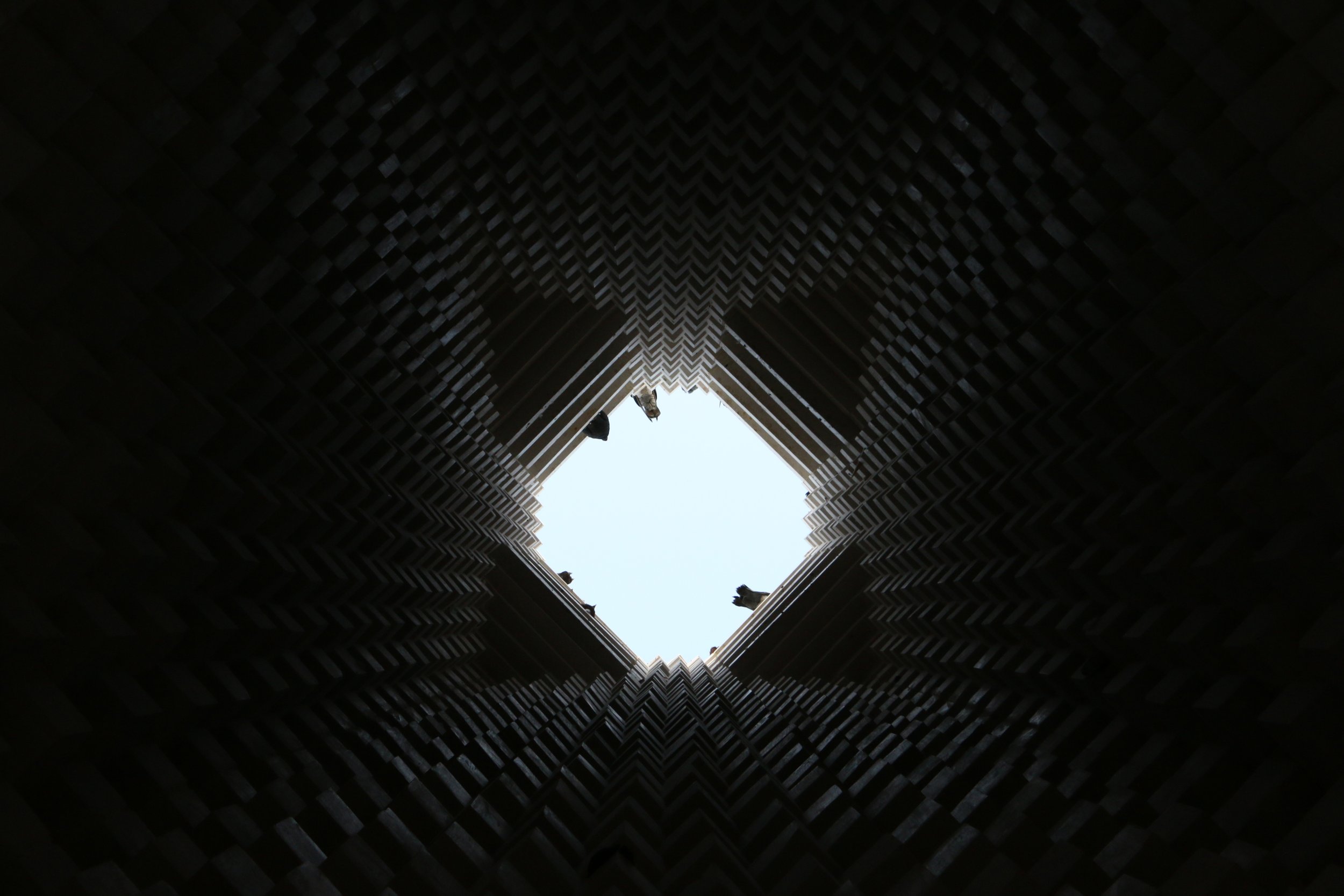

D One of my favorite projects is the Urban Pigeon Tower, built as part of Amman Design Week 2019. It is part of a bigger umbrella project that explores structures for urban wildlife and aims at bringing animals back into the realm of city planning and urban agriculture – a call to expand our urban compassion footprint and rewild the city as a rich multi-species ecosystem.

M How do you see the future of Tayyūn studio?

D I hope that we would be pushing the urban rewilding agenda to new frontiers: planting more forests, implementing new projects, and carrying out more research on urban biodiversity.

M What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned from this forest creation?

D Working with nature is a gentle yet firm call for patience, determination, and faith to trust the process.

M Any wishes you would like to share?

D I wish that we all take ownership of our problems and responsibilities, and come together to value and honor our land with a sense of pride, dignity and duty, recognizing its true potential. And then, anything is possible.

Urban Pigeon Tower installation at Amman Design Week, 2019.